The shock and trauma are evident in what women wove.

Women were then, and remain today, “the backbone of Lao society,” said Linda McIntosh, a textile specialist in Luang Prabang, Laos.

Women not only were in charge of managing the household and raising children; they were responsible for making all the family’s clothes.

Weaving was more than a chore. It was a form of expression.

Weaving gave women an outlet to express what they were thinking, about this life and the next.

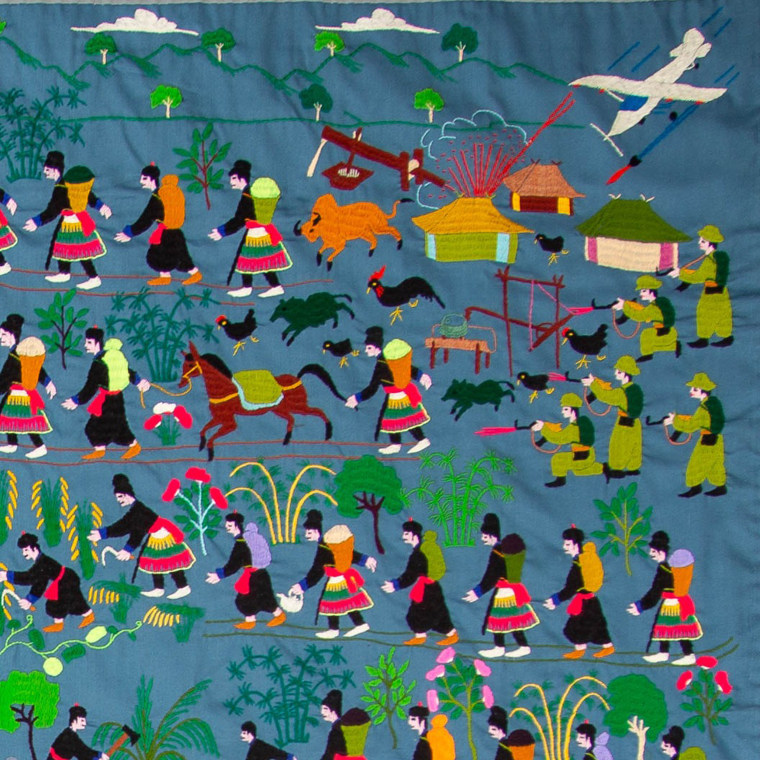

Traditional textiles blend symbols of the everyday, like rainstorms, birds and beetles, with those linked to the afterlife, like mangoes, elephants and ancestor deities.

“This is their vocabulary,” said Julia Brennan, who visits Laos regularly and whose company, Caring for Textiles, consults on preservation efforts around the world. “They’re not writing poetry or books or taking photographs. In the 1960s, the only channel they had was to weave stories into their own textiles.”

It was probably near the end of the war, McIntosh and Brennan said, that women began to incorporate martial themes: missiles, helicopters, tanks and fighter jets.

The women probably would have understood them not as state-of-the-art military technology but as powerful beings with immense power to kill and destroy, they said.

Weaving their likenesses into fabric, as with other spiritual entities, may have been an effort to ward off harm.

“It’s not just about pretty things,” McIntosh said. “Textiles are powerful. You put deities, you put gods, because they protect you.”

Weaving also had therapeutic value.

As the war concluded, thousands of Hmong families found themselves in refugee camps in neighboring Thailand.

It was there that Hmong women developed a tradition of story cloths: grand embroidered scenes of everyday life and the war that shattered it.

“There are many studies on textile-making and its benefits to mental health,” Pachia Lucy Vang, a Hmong American designer, said by email. “These forms of…

Read the full article here